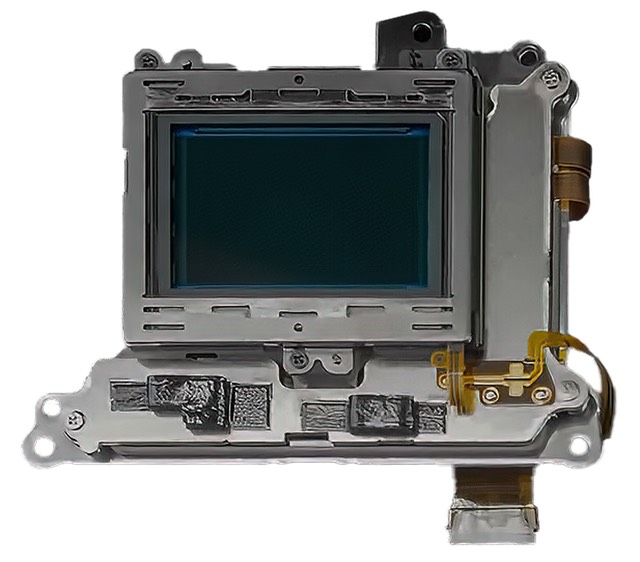

Nikon Z6III image sensor sits on a moving platform to provide stabilization

Back when sensor-based image stabilization—often referred to as IBIS (image sensor based image stabilization)—first appeared, there was an Internet frenzy over which was better, sensor-based or lens-based shake reduction. Marketing departments at camera/lens companies with vested interests in one answer or the other all fired up their mimeograph machines—uh, I mean marketing teams—and generated a great deal of contrary and confusing "information."

It's way past time to try to present a sane, reasonable explanation of the benefits and drawbacks of each type of image stabilization (IS).

First, here is something you need to know: IS does nothing for subject motion. Nothing. The Internet myths you might read such as "four stops of IS equals one stop of aperture or ISO" are something you need to just learn to ignore. If you need aperture (and ISO) to get a usable shutter speed to stop motion, you need aperture (or ISO to change shutter speed). Period.

At the other end of the spectrum, at high shutter speeds most IS systems at some point start to take away a bit of edge acuity. Why? It has to do with the frequency of the data sampling and the movement speed of the physical system versus how fast the shutter is moving (mechanical or electronic). For years I've been warning people to turn VR off—Nikon's form of lens-based IS—if you're photographing at high shutter speeds. Currently I assess that to be faster than 1/1000 second.

So image stabilization is a bit like antilock brakes on your car: when you need it, it's very useful. But you don't always need it.

Okay, so what do IS systems actually do? They do an excellent job of removing human-caused camera movement during an exposure. Sometimes wickedly so. I've handheld an OM-1 to one second and gotten a very usable shot of static subjects. IS systems also do a reasonable job with mechanical motion and vibrations. I've been rocked by boats, planes, trains, and more with wicked vibrations and bounces and gotten excellent images. I've had stadiums (stadia?) literally bouncing under my feet from fan excitement and still pulled off a sharp photo.

And, of course, as I get older, it's gotten more and more difficult for me to hand hold slower shutter speeds without seeing some impact. Whereas I used to be very comfortable pushing 1/15 handheld without IS one moderate telephoto lengths, now I'd say that 1/30 is my limit, and I try to stay above 1/60 if I can.

Lens versus Sensor Stabilization

Okay, so there are times when stabilization is useful. Should you get sensor or lens stabilization? Note: since I originally wrote this article, most of the makers are now doing both for long telephoto lenses. More on that in a bit.

Well, both approaches have their pluses and minuses. You should also note that the smart bet these days is on dual systems, which use both approaches. There's a reason for that.

A lens-based stabilization system generally is placed near the optical center of the lens (entrance pupil). The reason for this is that you get maximum shift ability with reasonably small lens elements and movement of them. The smaller the mass, the faster you can move it, and with less force (F = M*A, remember that formula?). Less force also means you don't need strong motors that use a lot of power, so the lens-based systems have tended to be reasonably kind on camera batteries.

Lens-based stabilization is helpful where the entire system (camera+lens) is rotating in its movement. The longer and heavier the lens, the more likely that the fulcrum point of motion is well forward of the camera body; but that's why the lens systems put the stabilization system at that point: you easily get the maximal correction. Update: I tend to think the improvement starts to be clearly seen for lens stabilization over sensor as you near 200mm focal length (full frame).

Moreover, with really long focal lengths, you are transcribing a very narrow angle of view overall. A 300mm lens sees about an 8° wide view. At a distance of 50’ (~15m) the field of view is about 6 feet (2m) on the long axis. I've seen people struggling to keep framing (and the focus sensor being used) within even a 6" side-to-side position on the subject, which translates to about 500 pixels on a 24mp camera. That's more than you can move the image sensor in any existing 24mp IBIS system I know of. Yet it is often within the range that a lens-based systems can deal with.

Lens makers use different acronyms for their lens based stabilization, which you'll see in the lens specification:

- Canon — IS (image stabilization)

- Fujifilm — OIS (optical image stabilization)

- Nikon — VR (vibration reduction)

- OM Digital — IS (image stabilization)

- Panasonic — OIS (optical image stabilization)

- Sigma — OS (optical stabilization)

- Sony — OSS (optical stabilization system)

- Tamron — VC (vibration compensation)

The problem with lens-based stabilization, whatever it is named, is that it adds cost and complexity to every lens. It also is restrictive in what it can steady. Vertical and horizontal shifts and rotations are easily handled by lens-based stabilization. Lens-based stabilization can't correct for camera roll, for instance, but sensor-based systems can.

One reason why DSLRs don't have sensor-based stabilization is that this wouldn't stabilize the viewfinder prior to taking an image, nor stabilize things for the focus system. A lens-based stabilization system does. A stabilized sensor by itself wouldn't keep autofocus systems aligned to the subject (the DSLR focus systems are forward of the image sensor, so don't get the stabilization benefit).

Mirrorless cameras, of course, use the image sensor to drive what the viewfinder shows and incorporate the focus system, so having on-sensor stabilization (again, typically referred to as IBIS, tends to mean that every lens you mount on the camera has some viewfinder stabilization active at all times (there may be some exceptions with adapted lenses on some systems).

The issue with IBIS is that it needs information about the lens to work correctly (thus the exception for some adapted lenses that aren't supplying the proper lens info). IBIS also has a modest range that it can correct, and it adds heat and mechanical complication at the most expensive part of the camera (image sensor).

Finally, IBIS tends to not disrupt bokeh in out of focus areas as much as lens-based stabilization sometimes does. Lens-based stabilization tends to distort optical paths a bit if the stabilization element isn't perfectly at the entrance pupil, while IBIS does not have that issue.

Of those, the problem with IBIS that is most important to note is the ultimate range limitation. That's why Canon, Nikon, Olympus, Panasonic, and Sony have now all gone to hybrid systems with telephoto lenses. In other words, lens-based stabilization coupled with sensor-based stabilization. This took us from the usual 5 stops (CIPA, see below) to the 8 stops improvement range.

Olympus also still warns about sensor cleaning potentially damaging their IBIS system. (Early Sony sensor-based systems were also easy to bust, but Sony later changed the design.) Nikon typically locks down the sensor (except for the Zf) when the camera is off or in cleaning mode, though they also disclaim physical sensor cleaning by the user. Fujifilm users should always turn IS MODE to OFF prior to physical sensor cleaning.

My big problem with image stabilization is this: some makers seem to be treating it as an "always on" feature. They often bury the only way to turn it on or off (or control other aspects of the stabilization performance) deep in some menu you'll not remember the location of. I disagree with that approach. I really want to escalate turning stabilization on and off as something I can get to without dropping into menus. As I hinted above, I believe that optimal image capture requires that you use stabilization conditionally, not all the time.

CIPA Ratings

Should you pay any attention to the CIPA ratings for stabilization?

Probably not. In practice, the CIPA stability ratings are just like the CIPA battery ratings: your mileage will vary. There's really never a dud in the bunch with CIPA stabilization testing, and any differences in rating don't typically speak to the more practical things you should be aware of.

For example, there is a difference between how well the various IS systems detect whether you're on a tripod or not—yet another reason why I want to take control of the stabilization setting—or whether you're panning with a subject and the stabilization should maximize a particular correction in that case. That's something I'm struggling to come up with a valid test for, but I do notice differences between the systems. My suggestion: turn stabilization off when the camera is on a stable support that’s not moving (e.g. tripod on solid ground), and learn whether your camera has a dedicated “panning mode” for IS and use that when panning. For instance, on Nikon cameras, the Sport mode is better for panning than the Normal mode. That's because the Nikon system is aggressive about re-centering the system on movement.

Beware using the CIPA numbers about how many stops the stabilization accomplishes when choosing a system. The CIPA tests are three-axis only and don't exactly mimic the situations you'd be using IS for. I've found that all the IS systems work well, but there's variability above and beyond what the CIPA numbers suggest.

The Different Stabilization Systems

Which brings us back to this:

- Canon IS— the RF cameras and lenses use both IBIS and lens stabilization. The older M cameras mostly used lens stabilization.

- Fujifilm OIS — a few bodies now have IBIS (e.g. X-H1, X-H2S, X-S20), some don't (e.g. X-T30). Some of the zooms and telephotos have OIS.

- Hasselblad — no stabilization.

- Leica — no stabilization.

- Nikon VR — IBIS for the Zf/Z5/Z6/Z6II/Z6III/Z7/Z7II/Z8/Z9, plus many adapted lenses have lens VR; the two work in conjunction. The Z9 added something called Synchro VR when both lens and camera have VR systems, which is now supported in other recent Nikons. For the Z30, Z50, Z50II, and Zfc, none have IBIS, but all the current DX zoom lenses have lens-based VR.

- Olympus/OMDS IS — originally Olympus only did IBIS, but OM Digital Systems, which took over the Olympus line, is making telephoto lenses with lens stabilization that works in conjunction with IBIS.

- Panasonic OIS — originally they had only lens stabilization, but are now including IBIS on most models (GH5s was an exception).

- Sigma OS — lens-based stabilization. May or may not work with camera's stabilization controls depending upon the age of lens. Current lenses work; some older lenses don't.

- Sony OSS — IBIS plus lens stabilization for telephoto lenses that works together.

- Tamron VC — lens-based stabilization. May or may not work with camera's stabilization controls depending upon age of lens. Current lenses work; some older lenses don't.

All else equal, I'd rather have IBIS (sensor based) than not, but I want that to work with lens stabilization for telephoto lenses, particularly for lenses that are 200mm (full frame) or longer. Typically, that not only gives you five axis correction (horizontal shift, vertical shift, roll, pitch, and yaw) but it also puts the correct type of axis correction at the place that does it best (shifts and roll on the sensor, pitch and yaw on the lens). Canon, Fujifilm, Nikon, Olympus, Panasonic, and Sony are now getting this (mostly) right, in my opinion.

But I also photograph a lot with stabilization turned off, particularly when I ‘m using high shutter speeds (>1/1000 second). I prefer that IS be settable by an external camera control, not buried in the menus (Nikon gets this right, at least with lenses that have VR switches).