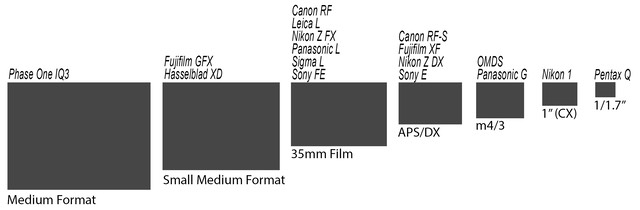

Mirrorless cameras come in a variety of sensor sizes:

Yep. There are (or have been) mirrorless cameras in all the above sensor sizes. At Small Medium Format both Fujifilm and Hasselblad have current cameras. These are either 50mp or 100mp. At FX (35mm film size) we've got Canon, Leica, Nikon, Panasonic, Sigma, and Sony. Those range from 12mp to 61mp models. At APS-C we've got the Canon, Fujifilm, Nikon, and Sony models. Here you'll find the range is 20mp to 40mp. At m4/3 both Olympus and Panasonic make a wide variety of models, which range from 20mp to 26mp. The Nikon 1 (what they also called CX) checked in at the next lower size. And at the bottom, we've had cameras like the Pentax Q and some of the old Ricoh GXR modules.

That image I show above is in scale, so the light collection area does vary considerably, doesn't it? So what size should you get?

All else equal, there are advantages of a larger sensor over a smaller one. Unfortunately, all else is rarely equal. Different sensor technologies have different fill factors, different efficiencies, and you may find they have different megapixel counts. So there is no simple answer, but some general ones to pay attention to.

Small Medium Format

Total image area: 1452 square mm

Both Fujifilm (GFX) and Hasselblad (X1D) have made mirrorless camera models with the Sony 50mp and 100mp "medium format" sensors (44 x 33mm). Medium format is in quotes in the previous sentence because most of us that remember medium format from the film era also remember a larger capture size (56 x 44mm). I therefore refer to the Sony 50mp/100mp sensors used in these cameras as "small medium format".

The small medium format is significantly larger than the old 35mm film frame (36 x 24). That means to get to equivalent lens values you need to multiply focal length by 0.79x. A "normal" lens for small medium format is in the 63-64mm range: Fujifilm has picked 63mm.

Both the Fujifilm and Hasselblad—as well as a few other cameras, such as the Pentax 645Z—all use the same Sony sensors, though Fujifilm claims that they've changed the layers just above the photocells (e.g. microlenses). These sensors are state-of-the-art Exmor-type and produce excellent data.

Full Frame (FX)

Total image area: 864 square mm

Full frame (FX in Nikon nomenclature) sensors are the same size as 35mm film was, give or take an eensy bit. If you're coming from a film camera or full frame (FX) DSLR, then full frame lenses all work as you'd expect them to. A 50mm lens is "normal." (Some will say 40mm, but that's a different discussion.) A 24mm lens gives you a 74 degree horizontal angle of view, just as it does on your older cameras.

Today we have Canon (RF), Leica (L), Nikon (Z FX), Sigma (L), Panasonic (L), and Sony (FE) all competing with state-of-the-art full frame sensors. You have more choice at this sensor size than any other. And yes, there is some variation in performance: in low light (e.g. the Sony A7S Mark III), in burst speeds (e.g. the Sony A9 Mark III), and in high pixel counts (e.g. the Canon R5, Nikon Z7 II and Z9, Panasonic S1R, and Sony A1 and A7R Mark V). Thus, you have to understand what you're trying to optimize for when picking a full frame mirrorless camera.

APS-C (DX)

Total image area: 384 square mm

The Canon (originally M, but now RF-S), Fujifilm (XF), Nikon (Z DX), and Sony (E) cameras all use APS-C sensors (as do some of the no-longer offered Ricoh GXR modules as well as the discontinued Samsung NX cameras). APS-C definitions have ranged from 1.5x (Nikon) to 1.7x (Sigma), with Canon in the middle at 1.6x. These are still relatively large sensors, and more to the point, most are very state-of-the-art. Since APS-C was the most popular DSLR sensor size for more than 20 years, a lot of engineering has been directed in the APS-C direction. (While technically all sensor engineering scales and isn't particularly size dependent, the large volume of APS-C sensor purchases have forced most of the basic sensor work tended to concentrate there first, and not in another of the sizes.)

Pretty much all of the APS-C sensor mirrorless cameras equal or exceed the image quality of the APS-C sensor DSLRs. Canon uses the same exact Canon-produced sensors in their mirrorless and DSLR models; Nikon did the same thing with their Z DX models, using the same excellent sensor as in the D7500 and D500, only with phase detect masking over the image sensor itself. Sony did the same thing with their models, using Sony 24mp sensors. Fujifilm uses a custom filtration system over two different Sony-supplied APS-C sensors (26mp and 40mp).

Most APS-C sensors have been 24mp, though we're now seeing higher pixel count ones. Nikon uses 20mp that has excellent low light tendencies. Practically, there's not a huge differential between the 20-26mp pixel counts that equates to clear resolution changes, though. Even Fujifilm's 40mp APS-C sensor requires the right lenses to take full advantage of that extra resolution.

Micro 4/3 (m4/3)

Total image area: 226 square mm

The first mirrorless cameras came from the transition from 4/3 (a DSLR-type design) to m4/3 (mirrorless) by Olympus and Panasonic. The Olympus Pen E-P1 and Panasonic GF-1 and GH-1 were the first widely available and fully fleshed out mirrorless cameras. Both companies have been rapidly iterating ever since (well over 40 different cameras have been produced over time!). Olympus eventually spun out their camera and lenses to OM Digital Solutions, which has continued the development of the line.

The 2x crop of the m4/3 sensor is slightly less than the same level of drop down from APS-C in size that APS-C is to full frame, though it comes with an aspect ratio change 4:3. If you crop to the same 3:2 aspect ratio, that really puts m4/3 a full stop below APS-C. m4/3 is still considered a large sensor compared to what's likely in your compact camera or cell phone.

The thing that makes the m4/3 size so interesting is that it's small enough so that the smaller imaging circle required of lenses clearly makes for...you guessed it...smaller lenses. The drop in size of lenses from full frame (FX) to APS-C (DX) isn't terribly dramatic, nor is the drop from an APS-C (DX) lens to m4/3 lens. But the difference between my Nikon full frame kit with a full range of lenses that cover 14mm to 400mm to my m4/3 kit with lenses covering the same angle of view is much more dramatic.

My biggest complaint about m4/3 used to be that Olympus was still using sensors that weren't really state-of-the-art when it was launched. That changed with the E-PM2, E-PL5, and OM-D E-M5 introductions, which had very state of the art sensors. The current OMDS lineup—again, the Olympus camera division was split out into a new company—uses new Sony-derived sensors. Panasonic also moved on to newer sensors that moved their image quality bar forward, as well.

Both OMDS and Panasonic have gone from 16mp to at least 20mp in most of their models, and are using basically the same technologies as in the APS-C sensors. There's less than a stop difference between APS-C/DX cameras and m4/3 cameras, all else equal, but you'll often be giving up a few pixels (20mp versus 24/26mp).

CX (Nikon 1)

Total image area: 116 square mm

One more step down in size—again about the same near one stop step as between each of the other adjacent sensor sizes—comes the now discontinued Nikon 1. While the smaller sensor size could have produced an even smaller body and lenses, in practice, many of the Nikon products in this format were nearer the smallest m4/3 camera size overall. The good news was that the Nikon 1 sensors were state-of-the-art in efficiency, so they tended to play above their league. Nikon once again showed that they know how to make very efficient sensors.

One thing to consider, though: the 1” sensor in the final Nikon 1 models is the same sensor as is used in many more recent Canon, Panasonic, and Sony compact cameras. Moreover, many of those fixed-lens models have better lenses than you got with the Nikon 1 kits. Personally, I wouldn't invest in Nikon 1 (CX) because of that, even if it were still being produced.

Compact

Total image area: varies, but Pentax Q was 25 square mm

If we step down yet again—slightly more than the steps we took in the other sensors we looked at, above—we get to sensors that were the size used in many compact cameras, especially older ones. The Japan-only Pentax Q and some of the no-longer-made Ricoh GXR modules have sensors in these very small sizes.

The problem with a small sensor size is that you're fighting a floor: there's a randomness to photons in the world. As you collect fewer and fewer photons, their randomness shows up as something usually referred to as shot noise. It doesn't matter how good the electronics are, noise is mostly generated simply from the randomness of light. These small sensors tend to be near enough that floor that shot noise is indeed a factor that needs to be always considered, even in brighter light.

When you buy a mirrorless camera with a sensor this small, you're essentially saying that you want a compact camera, but one that you can change the lens on. That's a perfectly valid point of view. Just make sure that it reflects your desires and needs.

But the Real Story Is…

You can see just how hard it is to make apples match up with apples when trying to compare sensors. I'm only three sensor sizes in and we've got three different levels of performance to consider. Not hugely dramatic differences, but enough to make you wonder if buying into one size or another is the right choice.

I'll save you some grief: unless you have a specific need don't get too worried about whether a sensor line exceeds or lags expectations. Those expectations are that APS-C is one stop behind full frame, m4/3 is less than a stop behind APS-C, and 1” is a stop behind m4/3. Going the other way, small medium format is perhaps a stop better than full frame.

Over time, things tend to equal out. Put another way: if you buy something that's slightly behind where it should be today, within a couple of years you'll have body upgrades available that will put you back to expected performance or even ahead. Likewise, if you buy something that's slightly ahead of the curve, the next bump might not be quite so interesting. These are system cameras, and it's all the components of the system together that are important. You're not buying a sensor, you're buying a camera body, a sensor, lenses, flash, remotes, and maybe even more accessories, and you're buying them over time.

However, the important thing we talk about in photographic circles in regards to sensors is "equivalency." What we usually mean by this is "what equipment and settings do we need to make the same exact image with different format cameras?"

To get equivalence in an image you need:

- Same position relative to the subject (i.e. you are not closer or further away from your subject)

- Same angle of view captured

- Same DOF captured

You'll also hear people talking about photons in regards to equivalence. Smaller sensors need faster lenses to let through the same number of photons and produce the same signal-to-noise ratio as do larger sensors. But I'm going to skip past this notion for this discussion and just assume that we're photographing in good light at base ISO with very good sensors for their size (i.e. noise and dynamic range aren't going to really impact our image).

We'll assume six photographers using different formats: small medium format, FX, APS-C, m4/3, Nikon 1, compact Coolpix P7100 (near the same as the mirrorless Pentax Q). I'm going to round the numbers a bit in values to the nearest common one, so don't get all picky on me here—I don't think the small amount of rounding is anywhere near as important as the basic concept. Again, we want equivalent photos as I've defined them above. So:

- Small medium format user is at 380mm f/10

- FX user is at 300mm f/8

- APS-C user is at 200mm f/5.6

- m4/3 user is at 150mm f/4

- Nikon 1 user is at 110mm f/2.8

Coolpix P7100 user is at 64mm f/1.8

Of course, we already have our first casualty: the Coolpix user doesn't have 64mm or f/1.8, as their fixed lens only goes to 42mm and f/5.6. Moreover, I've left off small medium format as there really aren't lenses that would be equivalent for it.

As we try to increase the angle of view, we start to limit options more:

- Small medium format user is at 63mm f/10

- FX user is at 50mm f/8

- APS-C user is at 35mm f/5.6

- m4/3 user is at 25mm f/4

- Nikon 1 user is at 18mm f/2.8

Moreover, the Nikon 1 user is down to basically one lens choice (the 18mm f/1.8). Let's go into a lower light situation and even wider:

- Small medium format user is at 31mm f/3.5

- FX user is at 24mm f/2.8

- APS-C user is at 16mm f/2

- m4/3 user is at 12mm f/1.4

Nikon 1 user is at 9mm f/1

We've now completely lost the Nikon 1 user and we're starting to lose the m4/3 and APS-C users, as any reasonable lens choice is starting to disappear (e.g. the OMDS user has a 12mm f/2, but not an f/1.4).

So, if our goal is to take pictures "that look just like we took them with 35mm film," then the equivalence notion starts putting restrictions on us, especially as we go to the extremes, like wider and faster. We just can't get to equivalence (and again, I'm not trying to bring photons and dynamic range into this discussion).

But the opposite is true, too. Let's turn things around and say that we want lots of depth of field:

- Coolpix user is at 6mm f/2.8

- Nikon 1 user is at 10mm f/4

- m4/3 user is at 14mm f/5.6

- APS-C user is at 18mm f/8

- FX user is at 28mm f/11

- Small medium format user is at 35mm f/15

Narrow the angle of view and try to keep a large DOF:

- Coolpix user is at 11mm f/5.6

- Nikon 1 user is at 19mm f/8

- m4/3 user is at 25mm f/11

- APS-C user is at 35mm f/16

- FX user is at 50mm f/22

- Small medium format user is at 63mm f/29

Hmm, the Nikkor 50mm lens only goes to f/16, so we're starting to lose the FX user! Moreover, diffraction comes into play with some of these options, as well.

The simple fact is that there are looks you can't get with small formats that you can with large formats, and vice versa. The trick is to pick the right tool for the right job, and therefore to understand the underlying differences of your tools. I don't use m4/3 to replace my FX equipment; I use m4/3 to supplement my FX gear. Yes, these at times overlap, in which case I can pick small/light or phenomenal dynamic range/noise properties (but not both ;~).

Everything in photography is about balancing decisions. Everything. You may make hundreds of decisions to get a single good photograph, and one of them is to choose the right tool for the job. I see the mirrorless cameras as just another tool. I wish the tool were better targeted towards me (more direct control, for example), but they do potentially offer me some options I didn't have before, so it's welcome.

I think a lot of the heat in the discussions about mirrorless cameras is the "I want something that can do everything" notion. People want small, light, inexpensive, high image quality, flexible, robust, and a few other things all in one package. But there's a simple fact of life: the more things you require from a tool, the more compromised and/or expensive it is. Moreover, some combinations are impossible (or at least improbable): small, inexpensive, and high quality, for example.